History Of Tea

Tea In China

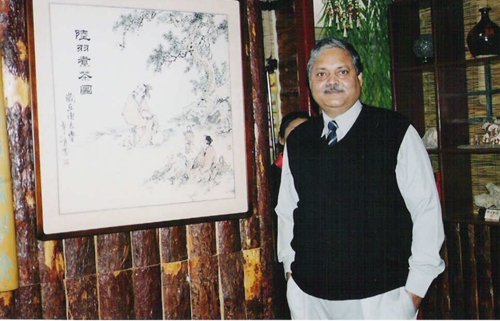

The popularity of tea spread. It took hold of every aspect of Chinese culture, especially through the influence of the Zen Buddhist tea masters. The monk Lu Yu (733-804) wrote the first definitive book on tea, called the Ch’a Ching, also known as the Classic of Tea in which Lu Yu presented information about Chinese tea culture. It is divided into three sections and ten chapters, including the tea’s origin tools, picking, ceremonies associated with tea and historical incidents of tea.

The effect of tea is cooling and as a beverage it is most suitable. It is especially fitting for persons of

self-restraint and inner worth.”

― Lu Yu, Classic of Tea: Origins and Rituals

Through years of wanderings and upheavals in his life, the monk Lu Yu spent a total of twenty-six years writing his famous book Ch’a Jing.

Tea in Japan

Tea in Japan is said to have begun with the appearance of the first tea seeds brought back to Japan from China by the Buddhist monk Eisai. At that time monks were using it for both calmness and staying awake during long meditation periods. Tea in Japan has always had the Buddhist influence and shown even in the popular tea ceremonies in Japan today. After a century or so tea became a popular luxury commodity among the Japanese nobility while the Japanese well-to-do languished under the cultural shadow of China.

A quote from writer and scholar Lofcadio Hearn (1850 –1904), known also by the Japanese name Koizumi Yakumo:

“The tea ceremony requires years of training and practice ... yet the whole of this art, as to its detail, signifies no more than the making and serving of a cup of tea. The supremely important matter is that the act be performed in the most perfect, most polite, most graceful, most charming manner possible.”

Today Japan produces green tea which is characterized by its color and its manufacturing process. Green tea is steamed in the manufacturing process and then dried, whereas black teas are fermented.

Tea in Europe

Portugal, with her technologically advanced navy, had been successful in gaining the first right of trade with China. As a missionary on that first commercial mission, Father de Cruz of Portugal was the first European to write about tea. The Portuguese developed a trade route by which they shipped their tea to Lisbon, and then Dutch ships transported it to France, Holland, and the Baltic countries. At that time Holland was politically affiliated with Portugal. When this alliance was altered in 1602, Holland, with her own excellent navy, entered into full Pacific trade in her own right.

Though concerned over developments in America, English tea interests still centered on the product's source-the Orient. There the trading of tea had become a way of life, developing its own language known as "Pidgin English". Created solely to facilitate commerce, the language was composed of English, Portuguese, and Indian words all pronounced in Chinese. Indeed, the word "Pidgin" is a corrupted form of the Chinese word for "do business". So dominant was the tea culture within the English speaking cultures that many of these words came to hold a permanent place in our language, such as mandarin, cash, caddy, and chow.

The East India Company (also known as the East India Trading Company, English East India Company, and, after the Treaty of Union, the British East India Company) was an early English joint-stock company that was formed initially for pursuing trade with the East Indies, but that ended up trading mainly with the Indian subcontinent and China.

The Opium Wars

Not only was language a problem, but so was the currency. Vast sums of money were spent on tea. To take such large amounts of money physically out of England would have financially collapsed the country and been impossible to transport safely half way around the world. With plantations in newly occupied India, the John Company saw a solution. In India they could grow the inexpensive crop of opium and use it as a means of exchange. Because of its addictive nature, the demand for the drug would be lifelong, insuring an unending market. Chinese emperors tried to maintain the forced distance between the Chinese people and the "devils". But disorder in the Chinese culture and foreign military might prevented it. The Opium Wars broke out with the English ready to go to war for free trade (their right to sell opium). By 1842 England had gained enough military advantages to enable her to sell opium in China undisturbed until 1908.

America Enters the Tea Trade

The first three American millionaires, T. H. Perkins of Boston, Stephen Girard of Philadelphia, and John Jacob Astor of New York, all made their fortunes in the China trade. America began direct trade with China soon after the Revolution was over in 1789. America's newer, faster clipper ships out sailed the slower, heavier English "tea wagons" that had until then dominated the trade. This forced the English navy to update their fleet, a fact America would have to address in the War of 1812. The new American ships established sailing records that still stand for speed and distance. John Jacob Astor began his tea trading in 1800. He required a minimum profit on each venture of 50% and often made 100%. Stephen Girard of Philadelphia was known as the "gentle tea merchant". His critical loans to the young American government enabled the nation to re-arm for the War of 1812. The orphanage founded by him still perpetuates his good name. Thomas Perkins was from one of Boston's oldest sailing families. The Chinese trust in him as a gentleman of his word enabled him to conduct enormous transactions half way around the world without a single written contract. His word and his handshake was enough so great was his honor in the eyes of the Chinese. It is to their everlasting credit that none of these men ever paid for tea with opium. America was able to break the English tea monopoly because its ships were faster and America paid in gold.

The Clipper Days

By mid-1800 the world was involved in a global clipper race as nations competed with each other to claim the fastest ships. England and America were the leading rivals. Each year the tall ships would race from China to the Tea Exchange in London to bring in the first tea for auction. Though beginning half way around the world, the mastery of the crews was such that the great ships often raced up the Thames separated only by minutes. But by 1871 the newer steamships began to replace these great ships.

Global Tea Plantations Develop

The Scottish botanist/adventurer Robert Fortune (1812-1880), who spoke fluent Chinese, was able to sneak into mainland China the first year after the Opium War. He obtained some of the closely guarded tea seeds and made notes on tea cultivation. With support from the Crown, various experiments in growing tea in India were attempted. Many of these failed due to bad soil selection and incorrect planting techniques, ruining many a younger son of a noble family. Through each failure, however, the technology was perfected. Finally, after years of trial and error, fortunes were made and lost, and the English tea plantations in India and other parts of Asia flourished. The great English tea marketing companies were founded and production was mechanized as the world industrialized in the late 1880s.

Tea Inventions in America: Iced Tea and Teabags

America stabilized her government, strengthened her economy, and expanded her borders and interests. By 1904 the United States was ready for the world to see her development at the St. Louis World's Fair. Trade exhibitors from around the world brought their products to America's first World's Fair. One such merchant was Richard Blechynden, a tea plantation owner. He had planned to give away free samples of hot tea to fair visitors. But when a heat wave hit, no one was interested in his hot tea, but to save his investment, he dumped a load of ice into the brewed tea and served the first "iced tea." Four years later, Thomas Sullivan of New York developed the concept of "bagged tea". As a tea merchant, he carefully wrapped each sample delivered to restaurants for their consideration. He recognized a natural marketing opportunity when he realized the restaurants were brewing the samples in the bags to avoid the mess of tea leaves in the kitchens.

Then: Tea Rooms, Tea Courts, and Tea Dances

Beginning in the late 1880's in both America and England, fine hotels began to offer tea service in tea rooms and tea courts. Served in the late afternoon, Victorian ladies (and their gentlemen friends) could meet for tea and conversation. Many of these tea services became the hallmark of the elegance of the hotel, such as the tea services at the Ritz (Boston) and the Plaza (New York). By 1910 hotels began to host afternoon tea dances as dance craze after dance craze swept the United States and England.

Now: In America tea’s popularity holds no bounds. In seeking a healthier lifestyle, many Americans are turning to the health benefits of tea. Along with hot tea iced tea is a regular staple beverage in American diets. Tea’s availability in America has increased with availability of information across the World Wide Web. Tea product information, related cultural subjects, even classes in tea – all have supported the world’s thirst for the leaf.

References:

The History of Tea, Mary Lou Heiss and Robert J. Heiss, 2007, Ten Speed Press

The Ultimate Tea Lover’s Treasury, James Norwood Pratt, 2011, Devan Shah and Ravi Sutodiya for the Tea Society, California and Kolkata